ARLINGTON, VIRGINIA — Boeing's changing fortunes: A potential return to dominance in China's Aviation Market.

Over the past few years, China has gradually approached unseating the US as the dominant force in the global commercial aviation industry, making it a crucial battleground for Boeing Co. By 2019, Chinese carriers, including China Eastern, China Southern and Air China, were increasingly carrying passengers nationwide and globally, resulting in China accounting for nearly a third of all Boeing 737 purchases. Despite Airbus SE setting up an assembly line in Tianjin in 2008, Boeing still held the majority of China's airspace. It seemed that if China wished to maintain its expanding air travel industry, it needed Boeing's aircraft.

However, two fatal crashes involving Boeing's 737 MAX, the most modern version of the aircraft, led global regulators to ground the model. Escalating trade disputes with the US and China's strict COVID-19 lockdowns further reduced China's interest in purchasing from the leading US exporter, causing a sharp decline in orders from Boeing's largest foreign market. It soon seemed that Boeing needed China more than China needed Boeing.

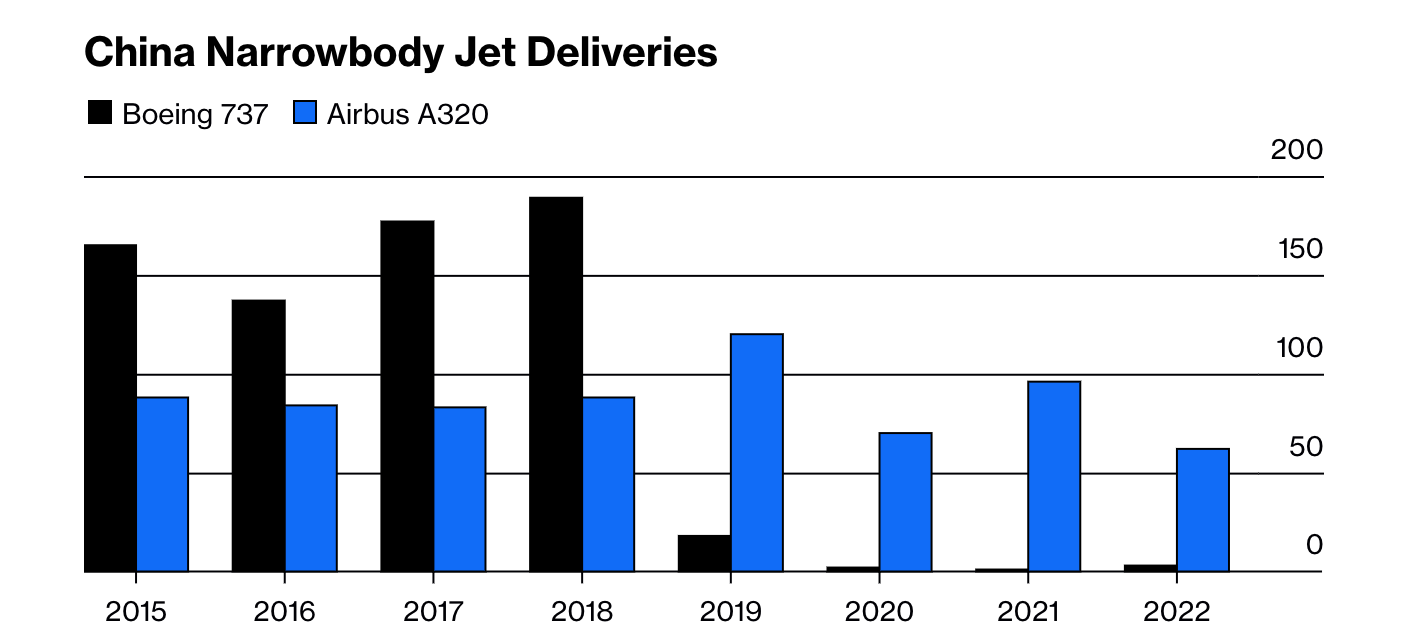

Since 2020, Airbus has delivered 384 aircraft to China, compared to Boeing's mere four, according to research firm Cirium. Following a deal in July to sell 292 planes to China, Boeing lamented the "geopolitical differences" preventing its aircraft exports, noting that $10 billion worth of aircraft, primarily 737s, designated for China were in a standstill. By September, Boeing was marketing these aircraft to other buyers, with CEO Dave Calhoun voicing his impatience. "You've got to move them," he said. "You can’t wait forever."

However, over the past few months, Boeing's situation in China has improved. Following the removal of the government's pandemic restrictions in January and the subsequent resumption of 737 MAX flights, travel has nearly returned to pre-COVID levels. Despite ongoing tensions between the US and China over trade, tariffs, and Taiwan, Boeing executives are growing confident that its aircraft could soon return to Chinese buyers. Calhoun suggests there is "momentum toward more commerce."

As the aviation industry recovers, new jetliners are becoming scarce. Both the Max and Airbus's models are sold out until 2027 and later, and after three years of lockdowns, China's citizens are eager to travel, yet airlines face a lack of aircraft to transport them, tipping the power balance back toward Boeing.

Meanwhile, worldwide carriers are securing future delivery slots. Ryanair Holdings Plc has orders for up to 300 MAX jets set to fly between 2027 and 2033. United Airlines Holdings Inc. purchased 200 Dreamliners, Boeing's most advanced widebody aircraft, and 100 737s in December. Air India Ltd. has committed to hundreds of aircraft to refresh its fleet, with the first planes arriving this year. Newcomer Riyadh Air from Saudi and Turkish Airlines are negotiating their own large orders as they plan for growth.

The scarcity of aircraft is further exacerbated by the supply chain still recuperating three years after the pandemic disrupted global markets. Airbus twice had to reduce its delivery targets in 2022, resulting in fewer delivered jets and intensifying an already tight supply. Calhoun predicts the sellers' market for planes will last for another half-decade due to continuing shortages of seats, engines, and other components until next year's end.

Although Airbus still maintains its lead in China and globally built during Boeing's MAX crisis, it will take many years before Commercial Aircraft Corp. of China, the country's native plane maker, can truly compete with Boeing, according to Cirium's Rob Morris. This won't happen until China's C919, its response to the MAX, can demonstrate its reliability under heavy daily usage and mass production. Therefore, Chinese airlines may need to start ordering the MAX to meet rising passenger demand. Morris says, "I do see a credible path for Boeing to regain some element of market share in China, even if politics seem to be a huge roadblock."

Since January, Chinese carriers have retrieved about two-thirds of the 97 MAX planes they own from storage. In April, the national aviation regulator removed the remaining technical obstacles to resuming deliveries of the 140 aircraft in Boeing's storage. Calhoun says that the final step to restarting MAX exports is for China's central economic planning agency "to simply say, 'Deliver the airplanes.'"

To improve Boeing's financial health by mid-decade, Calhoun has developed plans even if the trade stalemate with China continues. The key will be to rev up Boeing's factories without quality issues and production glitches, problems that the company continues to face. However, to boost deliveries of the 737 and the 787, Boeing will need to jump-start sales to China. Seth Seifman, a JPMorgan Securities LLC analyst, notes that prior to the pandemic, China's airlines were significant buyers of the Dreamliner, in addition to purchasing hundreds of single-aisle planes. He says, "Over time it is important for Boeing to get back there. Not just for the 737, but in terms of widebody orders."